Coolant vs. Raw Water Cooling: Understanding Outboard Systems

- Raw Water Cooling: How It Works

- Closed-Loop Coolant Cooling: How It Works

- Air-Cooled Outboards

- Choosing the Right System for Your Use

- Identifying Your Cooling System

- Winterization and Antifreeze

- Troubleshooting Overheating

- Parts Quality: OEM vs. Aftermarket

- Maintenance Costs: Raw Water vs. Closed-Loop

- How to Identify Heat Exchanger Leaks

- Flushing Ports vs. Muffs

Most outboards use one of two liquid cooling methods: raw water or closed-loop coolant. If you run in salt, you need to understand the difference because it dictates how long your motor lasts and what you'll spend on repairs.

Raw Water Cooling: How It Works

Raw water systems pull whatever you're floating in—lake water, river water, saltwater—straight into the lower unit through intake ports. The impeller pumps it up through the block, around the cylinders, through the exhaust manifolds, then spits it overboard mixed with exhaust. Simple. No heat exchanger, no coolant reservoir, no expansion tank. Just water in, heat out.

The tell-tale stream is your diagnostic tool. That little piddle of water out the back of the cowling shows the pump is working. If it's strong and steady, you're moving water. If it dribbles at idle but improves with throttle, check your impeller for a partially seized vane. If it stops completely, shut down immediately—you're running dry and the block temperature is climbing fast.

Raw Water Pump and Impeller Function

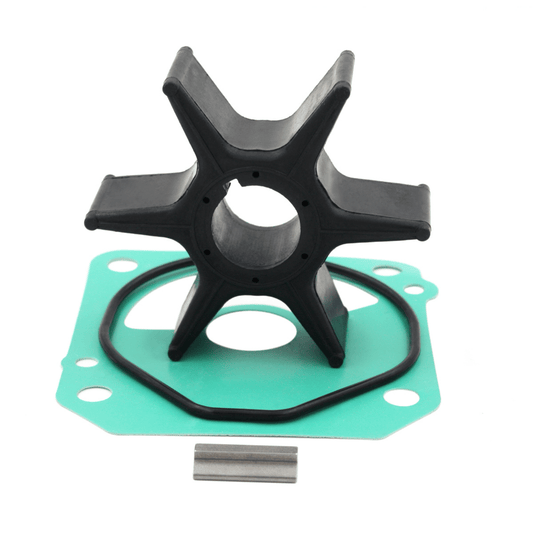

The impeller sits in the lower unit, driven by the driveshaft. It's rubber with flexible vanes that bend as they spin, creating suction on one side and pressure on the other. Water gets pulled in, forced up through the mid-section, and routed to the block. The impeller takes a beating. Vanes develop memory—they take a permanent set in the direction of rotation. When that happens, pumping efficiency drops and flow weakens even though the impeller hasn't "failed" yet.

We pull impellers every two years or 100-200 hours, whichever comes first. In saltwater, lean toward annual replacement. When you pull one, check for missing vane tips, cracks at the base, or a glazed surface that feels hard instead of pliable. If it smells like burnt rubber, you ran dry at some point.

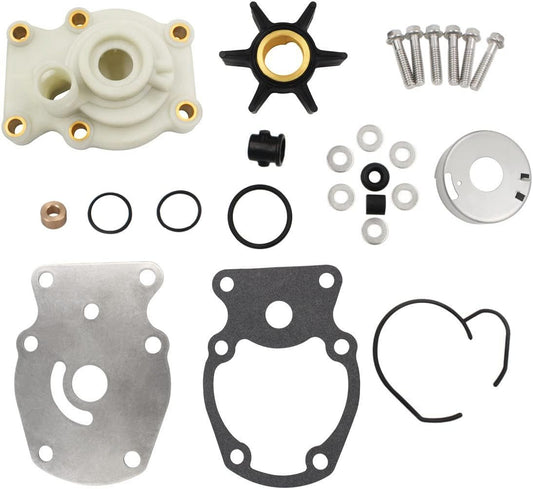

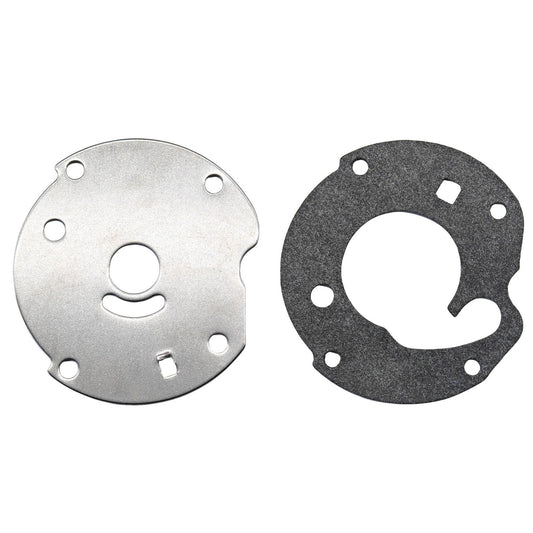

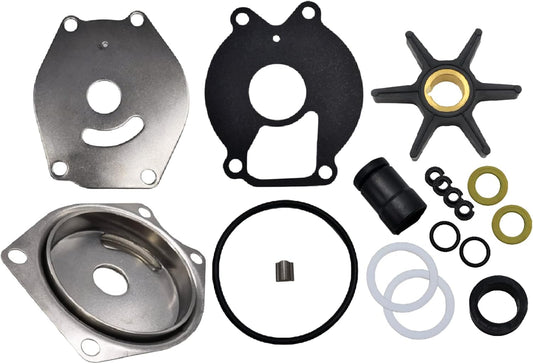

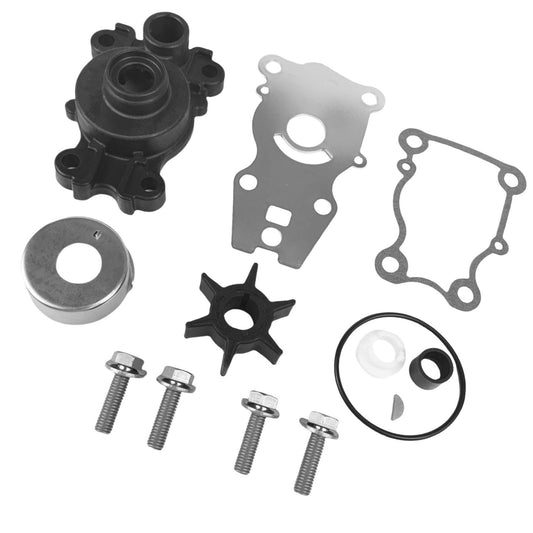

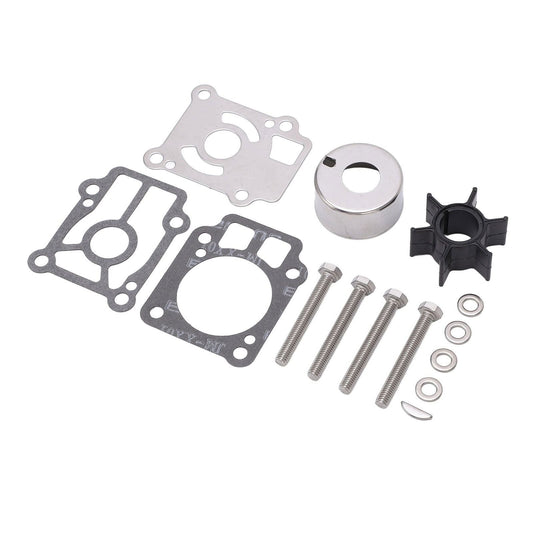

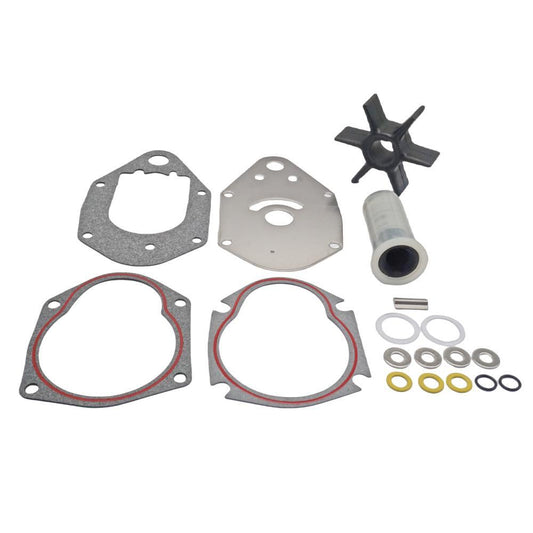

Impeller replacement on most Yamaha and Mercury lower units requires a 10mm or 12mm socket for the pump housing bolts. Use penetrating oil if you're in salt—those bolts corrode in place. The housing gasket is single-use; order a new one with the impeller. JLM Marine kits include the gasket, impeller, and wear plate insert so you don't have to piece it together. For more details on water pump upkeep, see our Water Pump Repair Kit vs. Impeller Only guide.

Thermostat in Raw Water Systems

The thermostat sits where water exits the block, usually in the cylinder head or a dedicated housing bolted to the head. When cold, it stays closed and restricts flow so the engine warms up faster. Once the block hits around 140-160°F, the thermostat opens and lets water circulate freely.

Stuck-closed thermostats cause rapid overheating—the block has nowhere to dump heat. Stuck-open thermostats prevent the engine from reaching proper operating temperature, which kills fuel economy and causes incomplete combustion. You'll see black smoke and fouled plugs.

To check a thermostat, pull it and drop it in a pot of water with a thermometer. Heat the water slowly. The thermostat should start opening right around its rated temperature, typically stamped on the body (140°F or 143°F are common on outboards). If it doesn't move or stays fully open, replace it. For step-by-step thermostat replacement help, refer to How to Replace the Thermostat on Your Yamaha F225, F250, or F300 4.2L V6 Outboard Motor.

If you suspect a stuck thermostat but don't want to tear it down yet, use an infrared thermometer on the cylinder head near the thermostat housing. Compare that reading to the lower cowling or lower unit temperature. If the head is 200°F+ and the lower cowling is cool, the thermostat isn't opening. Saltwater accelerates thermostat corrosion. We see them seize every 2-3 years in coastal environments. Replacement is cheap insurance; a new thermostat costs $20-40 and takes fifteen minutes. A cooked powerhead costs thousands.

Raw Water Corrosion and Scale

Saltwater is nearly as corrosive as acid, especially in warm climates like Florida or Southern California. When raw water runs through the block above 140°F, dissolved salts precipitate out and form hard scale on internal passages. This scale builds up over years, restricting flow and creating hot spots. Eventually, flow drops so low that the engine overheats even with a new impeller and open thermostat.

At that point, you're looking at a block replacement or a complete rebuild. Flushing after every saltwater trip slows this down but doesn't stop it. The best defense is religious flushing with fresh water. Use flush muffs or a flush port if your motor has one. Run the engine for 10-15 minutes at idle with fresh water flowing to rinse out salt deposits before they crystallize. You can find more about proper flushing methods in our Outboard Overheating 101: Quick Checks to Prevent Damage article.

Brackish water—common in estuaries, bays, and coastal rivers across the U.S.—is just as bad. It carries silt, organic matter, and dissolved minerals that clog strainers and coat passages. If you run in brackish conditions, pull and clean your raw water strainer every 20-30 hours. It's a mesh or perforated basket in the water line before the pump. Debris here chokes flow before it ever reaches the impeller.

Closed-Loop Coolant Cooling: How It Works

Closed-loop systems run a sealed circuit of antifreeze and water inside the engine. The coolant circulates through the block and heads via a dedicated coolant pump, absorbs heat, then flows to a heat exchanger. The heat exchanger is where the magic happens: hot coolant runs through one set of internal tubes, and raw water from the lower unit runs through a separate set. Heat transfers from the coolant to the raw water without the two ever mixing. The cooled coolant returns to the engine, and the warmed raw water gets dumped overboard with the exhaust.

This design isolates the engine internals from corrosive water. Saltwater never touches the block, cylinders, or head. It only contacts the heat exchanger tubes and exhaust components. The result is drastically reduced internal corrosion and longer engine life, especially in saltwater.

Typical closed-loop systems maintain engine temperature between 160°F and 180°F with a variance of ±5°F, much tighter than raw water systems, which fluctuate with ambient water temperature. In cold northern lakes in spring, a raw water motor might run at 120°F. In the Gulf of Mexico in August, the same motor might hit 190°F. Closed-loop keeps it stable.

Closed-Loop Components and Maintenance

A closed-loop system adds several components: an expansion tank (coolant reservoir with a pressure cap), a heat exchanger, internal coolant hoses, and a thermostat that regulates coolant flow instead of raw water flow. The expansion tank is usually mounted high on the engine and has minimum/maximum level marks. Check it cold; the level should sit between those marks. If it's low, top it off with a 50/50 mix of marine-grade ethylene glycol antifreeze and distilled water.

Never use automotive antifreeze in a marine engine. Marine formulations include corrosion inhibitors specific to aluminum and dissimilar metals common in outboards. Automotive antifreeze can accelerate galvanic corrosion. Learn why you should avoid car parts in marine engines in our detailed post, Can I Use Automotive Parts in My Boat Engine?

Change the coolant every two years. Old coolant loses its corrosion protection and its ability to transfer heat efficiently. Draining is straightforward: locate the drain petcock on the block or pull the lower coolant hose at the heat exchanger. Flush with distilled water, then refill with fresh 50/50 mix. Burp the system by running the engine with the expansion cap off until no more air bubbles come out, then top off and reinstall the cap.

The heat exchanger is the weak point. Scale and debris from raw water can clog the raw-water side of the exchanger over time. Symptoms are the same as a clogged block in a raw water system: overheating despite good coolant flow. To check, feel the heat exchanger body while the engine is running. If the raw water outlet is cool but the coolant inlet is hot, the exchanger isn't transferring heat—it's clogged.

Heat exchangers can often be cleaned chemically. Remove it, flush it backward with a dilute acid solution (muriatic acid or dedicated descaler), then rinse thoroughly. If the tubes are corroded through or the exchanger is leaking internally (coolant mixing with raw water), replace it. A replacement heat exchanger costs $200-600 depending on size. That's cheaper than a new block, which is the equivalent repair cost in a raw water system with a scaled-up block.

Pressure-test the system annually. Use a cooling system pressure tester on the expansion tank cap. Pump it to the cap's rated pressure (typically 15 psi) and watch for leaks at hose connections, the heat exchanger, or the head gasket. A slow pressure drop indicates a leak. Fix it before it becomes a catastrophic overheat.

Why Closed-Loop Costs More

Closed-loop systems add cost and weight. The heat exchanger alone adds 10-20 pounds. Extra hoses, clamps, coolant pump, and expansion tank bring more complexity. Initial purchase price on a closed-loop outboard or sterndrive runs $1,000-3,000 higher than an equivalent raw water model.

But in saltwater, the payoff is clear. A raw water block might last 8-10 years in salt before scale buildup forces a rebuild. A closed-loop system regularly sees 15-20 years with proper coolant changes. We've seen 25-year-old MerCruiser sterndrives with closed cooling and clean, rust-free blocks. The equivalent raw water model would have been scrapped a decade earlier.

If you boat exclusively in freshwater and flush diligently, raw water is fine. If you spend time in salt or brackish water, closed-loop pays for itself in engine longevity.

Air-Cooled Outboards

Smaller outboards—2.5 HP to 6 HP—often use air cooling instead of water. Cooling fins cast directly into the cylinder and head dissipate heat. As the boat moves, airflow over the fins carries heat away. No pump, no impeller, no water passages. Dead simple.

Air-cooled motors perform best at speed, where airflow is strong. At idle or low speeds, especially on a hot day, they can get warm. Chronic overheating shows up as discoloration or bluing on the cooling fins, warped cylinder heads, or seized pistons.

Keep the fins clean. Grass clippings, mud, leaves, and spider webs pack into the fin gaps and block airflow. Once a month, pull the cowling and brush out the fins. A soft brush and a garden hose work fine. Make sure the air intake vents on the cowling are clear—these vents direct air over the fins, and blocking them kills cooling efficiency.

Air-cooled outboards are common on jon boats, dinghies, and inflatables where weight and simplicity matter more than ultimate power. They're also popular in shallow, weedy water where a raw water intake would clog constantly.

Choosing the Right System for Your Use

If you run in freshwater lakes and rivers, a raw water outboard is the standard. It's light, cheap, and effective. Flush after every trip and replace the impeller on schedule, and it'll last.

If you run coastal, in bays, or in saltwater, a closed-loop system is worth the extra cost. The reduction in corrosion alone justifies the price. If you already own a raw water motor and run in salt, increase your flushing frequency and consider a saltwater corrosion inhibitor spray on external components.

For shallow, debris-filled water, air-cooled or raw water with a well-placed intake screen is your best bet. Closed-loop systems still rely on raw water for the heat exchanger, so they're just as vulnerable to clogged intakes as raw water systems.

For performance applications—racing, heavy towing, sustained high RPM—closed-loop offers better temperature stability. Consistent engine temp means consistent fuel mapping and ignition timing, which translates to reliable power output.

Identifying Your Cooling System

If you don't know which system you have, here's how to check. Pull the cowling and look for a plastic expansion tank with a pressure cap—that's closed-loop. If you see no tank and no coolant hoses inside the cowling, it's raw water. On the lower unit, both systems will have water intake ports, so that doesn't tell you much.

If you see a heat exchanger—a cylindrical or rectangular metal component with hoses on both ends—you've got closed-loop. Heat exchangers are usually mounted low on the block or in the mid-section. If there's nothing between the raw water pump outlet and the block, it's raw water.

Winterization and Antifreeze

In freezing climates, winterization is mandatory. For raw water systems, drain all water from the block and flush lines. Some techs run the engine briefly with a bucket of non-toxic marine antifreeze (propylene glycol) to displace residual water in passages and the exhaust. Never use automotive antifreeze for this—it's toxic and will kill fish if it leaks into the water.

For closed-loop systems, the internal coolant already contains antifreeze and provides freeze protection year-round. You still need to winterize the raw water side of the heat exchanger. Drain the raw water circuit and run antifreeze through it, just like a raw water system.

The key difference: closed-loop antifreeze (ethylene glycol or propylene glycol mixed 50/50 with water) stays in the system and provides corrosion protection. Raw water winterization antifreeze is a one-time flush to prevent ice damage, then it's expelled on the first spring startup.

Troubleshooting Overheating

If your motor overheats, start with the easiest checks. Is the tell-tale stream flowing? If not, check for debris in the lower unit intake. Pull the lower unit and inspect the impeller. Look for broken vanes, a seized impeller shaft, or a worn impeller housing. For a detailed guide on impeller signs and replacement, see Signs Your Outboard Impeller Needs Replacement.

If the tell-tale flows but the engine still overheats, check the thermostat. Pull it and bench-test it in hot water. If it opens, reinstall it and move on.

For closed-loop systems, check coolant level in the expansion tank. If it's low, you have a leak. Pressure-test the system and inspect hoses, the heat exchanger, and the head gasket.

If coolant level is good but the engine overheats, the heat exchanger may be clogged. Feel the raw water outlet on the exchanger while running. If it's barely warm, raw water isn't flowing through. If it's hot, the exchanger is clogged internally and not transferring heat.

For raw water systems with good flow and a working thermostat, the block may be scaled up. At that point, you're looking at a block flush with descaling chemicals or, in severe cases, a rebuild.

Parts Quality: OEM vs. Aftermarket

OEM impellers and thermostats are good quality, but you're paying a premium for the brand name on the box. At the dealer, a Mercury impeller kit runs $60-80. The same kit from a reputable aftermarket supplier like JLM Marine runs $25-40 and uses the same factory-spec rubber and tolerances.

Avoid no-name $10 impeller kits from random online sellers. The rubber is too hard, the vanes are dimensionally off, and they fail within a season. We've pulled apart motors where cheap impellers shredded after 20 hours and sent chunks of rubber through the cooling passages, clogging everything downstream. It's not worth the headache.

High-quality aftermarket parts often come from the same factories that produce OEM components. These factories use excess capacity to manufacture non-OEM parts that meet identical specifications. JLM Marine sources from these facilities, so you get OEM fitment and durability without the dealership markup.

For thermostats, gaskets, and pump housings, the same logic applies. OEM is reliable but expensive. Quality aftermarket saves money without sacrificing performance. Low-end aftermarket is a gamble that usually costs you more in the long run.

Check out our extensive Cooling System Parts collection for OEM-quality components direct from the factory.

Maintenance Costs: Raw Water vs. Closed-Loop

Over five years, here's what typical maintenance looks like:

Raw Water System (Saltwater Use)

- Impeller replacement (annual): 5 × $40 = $200

- Thermostat replacement (every 2 years): 2 × $30 = $60

- Descaling service or block flush (once): $150-300

- Total: ~$410-$560

Closed-Loop System (Saltwater Use)

- Impeller replacement (annual, raw water side): 5 × $40 = $200

- Thermostat replacement (every 2 years): 2 × $35 = $70

- Coolant changes (every 2 years): 2 × $50 = $100

- Heat exchanger cleaning or replacement (if needed): $0-$400

- Total: ~$370-$770

Closed-loop has higher maintenance costs, but it avoids the catastrophic block replacement that raw water systems face after years of scale buildup. A new powerhead costs $3,000-8,000. A heat exchanger costs $200-600. The math favors closed-loop in saltwater.

In freshwater with diligent flushing, raw water systems rarely need descaling, so the five-year cost drops to around $260. Closed-loop still costs more but offers better temperature control and freeze protection.

How to Identify Heat Exchanger Leaks

Internal heat exchanger leaks let coolant mix with raw water. Symptoms include low coolant level in the expansion tank, coolant smell in the exhaust, or white steam (not normal water vapor) from the exhaust.

To confirm, pull the raw water outlet hose from the heat exchanger while the engine is off. Taste or smell the water inside. If it's sweet or smells like antifreeze, the exchanger is leaking internally. Replace it immediately. Running with a leaking exchanger will overheat the engine and contaminate the water.

External leaks show up as coolant drips under the engine or wet spots on hoses and connections. Pressure-test the system to find the exact location.

Flushing Ports vs. Muffs

Most modern outboards have a dedicated flushing port—a threaded fitting on the lower unit where you attach a garden hose. Turn on the water, and it flows directly into the cooling system without running the engine. This is the safest, easiest way to flush.

Older motors require muffs—rubber cups that fit over the lower unit intake ports. You attach a hose, turn on the water, then start the engine to pump water through the system. Muffs work but have drawbacks: if they slip off during flushing, you run the engine dry and cook the impeller. If water pressure is too high, you can blow seals in the lower unit.

If your motor has a flush port, use it. If you're stuck with muffs, watch the tell-tale stream the entire time the engine is running. If it weakens or stops, shut down immediately.

Check the lower unit intake screens every time you flush. They're the small grills or ports on the sides of the lower unit. Weeds, plastic bags, and fishing line get sucked in and block flow. A zip tie or small screwdriver will pull most debris out. In heavy weed areas, check after every trip.

When you start your engine, make it a habit to glance at the tell-tale stream within the first 30 seconds. Strong and steady means the pump is working. Weak or absent means you need to shut down and investigate before you cook the powerhead.

For more tips on impeller maintenance and troubleshooting, see How Often Should You Replace Your Outboard’s Impeller?.

Explore our full range of boat accessories and parts at JLM Marine, your trusted source for premium marine components with free worldwide shipping. For more comprehensive information about boating parts and maintenance, visit the JLM Marine home page.

About JLM Marine

Founded in 2002, JLM Marine has established itself as a dedicated manufacturer of high-quality marine parts, based in China. Our commitment to excellence in manufacturing has earned us the trust of top marine brands globally.

As a direct supplier, we bypass intermediaries, which allows us to offer competitive prices without compromising on quality. This approach not only supports cost-efficiency but also ensures that our customers receive the best value directly from the source.

We are excited to expand our reach through retail channels, bringing our expertise and commitment to quality directly to boat owners and enthusiasts worldwide.

Leave a comment

Please note, comments need to be approved before they are published.