Choosing Impeller Material: Rubber vs. Neoprene vs. Plastic

- Material Basics: What You're Actually Buying

- Temperature Limits: What Happens When It Gets Hot

- Run-Dry Tolerance: What Survives a Blocked Intake

- Abrasion and Tear Resistance: Matching Material to Grit

- Oil and Chemical Exposure: The Hidden Killers

- Flex-Crack Resistance: Why Impellers Fracture

- Cost vs. Longevity: What You Actually Pay

- Identifying What You Currently Have

- How to Choose: Step-by-Step

- Material and Fit: Hardness Matters for Installation

- Avoiding OEM and Cheap Aftermarket Traps

- Quick Decision Matrix

Your raw water pump is spitting weak at idle but picks up at throttle. Or your bilge pump just quit mid-season. Nine times out of ten, it's the impeller. The material you pick for the replacement decides whether you're back out next weekend or tearing into that pump housing again in three months.

After twenty years wrenching on outboards, I've pulled hundreds of failed impellers. The guys who grab whatever's cheapest always come back. The ones who match the material to the job don't. Here's how to pick right.

Material Basics: What You're Actually Buying

These three materials aren't swappable. Each one behaves differently under heat, chemicals, and wear.

Natural Rubber

Natural rubber comes from tree sap—Hevea brasiliensis. Raw latex is soft and degrades fast, so manufacturers vulcanize it by adding sulfur and heating it. This cross-links the polymer chains, making it tougher and heat-stable.

That sulfur is also why natural rubber fails around oil. The sulfur bonds react with petroleum products, causing the rubber to swell and soften. It's chemistry, not poor quality.

Natural rubber handles impact well. If you're pumping fine sediment or neutral slurries—think sandy harbor water with rounded particles—it absorbs shock without tearing. But it has limits: temps over 70°C per standard slurry pump guidance, and any oil exposure will kill it.

Tear Resistance: Excellent for blunt forces.

Heat Tolerance: Under 70°C before it softens.

Chemical Weakness: Oils, fuels, ozone, UV—all attack it.

Neoprene (Polychloroprene)

Neoprene is synthetic. It's lab-made from chloroprene monomers, not tree sap. That chlorine in the molecular structure gives it oil and chemical resistance that natural rubber can't touch.

It's the default for marine raw water pumps because it handles saltwater, mild diesel contamination, and temperature swings without breaking down. Neoprene also resists flex-cracking—the tiny stress fractures that form when an impeller bends thousands of times. In oily or contaminated water, neoprene lasts 1-2 times longer than natural rubber per slurry pump data.

One thing to watch: some diesel mechanics prefer nitrile over neoprene in fuel-heavy environments. A mechanic on a UK boating forum noted that stagnant diesel residue in marina bilges attacks neoprene over time. Stagnant exposure is worse than flow because the chemical sits concentrated on the rubber instead of washing through. If your bilge regularly has fuel puddles sitting for weeks, nitrile might edge out neoprene.

Flex-Crack Resistance: Superior. Handles constant bending.

Heat Tolerance: Up to 90°C per technical guidelines.

Chemical Strength: Good with oils, saltwater, mild acids. Weaker against strong solvents and gasoline.

Engineering Plastics (Polyurethane & Rigid Polymers)

"Plastic impeller" usually means polyurethane for flexible types or reinforced composites for rigid ones. Polyurethane is flexible, like rubber, and molds into vanes. Rigid plastics like nylon or reinforced fiberglass are used for housings or non-flexing impeller designs—not the flexible vane type most boaters replace.

Polyurethane dominates U.S. residential pumps—sump pumps, pool pumps, light-duty transfer pumps. It's corrosion-proof, lightweight, and cheap to mold. In clean freshwater with fine abrasives like silica, polyurethane lasts 3-5 times longer than natural rubber because of its high durometer (hardness) and cut resistance per industrial slurry tests.

But toss sharp, coarse grit at it—crushed shell, gravel, metal filings—and it chips. Polyurethane is brittle under impact compared to rubber's elastic give.

A case study on a carbon fiber composite impeller showed catastrophic failure when temps hit 80°C with a blocked inlet. The vinyl ester resin lost 25-40% of its strength. Plastics have hard temperature ceilings. Most flex around 70-90°C depending on formulation.

Abrasion Life: Excellent in fine, clean media. Poor with sharp debris.

Temperature Range: 70-90°C for most grades.

Chemical Resistance: Extremely broad. Inert to most acids, salts, and water. Some solvents can soften specific polymers.

Temperature Limits: What Happens When It Gets Hot

Heat kills impellers. Here's what actually happens inside each material when temps climb.

Natural rubber starts losing stiffness above 70°C. The vulcanized cross-links begin reversing, and the impeller gets gummy. Pull one out after overheating and it'll feel sticky, almost like it's melting back to raw latex.

Neoprene holds shape up to about 90°C per material selection charts. Past that, it hardens and cracks instead of softening. A hard, cracked neoprene impeller won't seal—it'll let water slip past the vanes.

Plastics vary. Polyurethane usually fails around 70-90°C. The failure mode is different: the polymer chains break, and chunks start chipping off. In the composite impeller failure I mentioned, temps over 80°C caused structural collapse because the resin binder degraded.

If your engine runs over 180°F (82°C) at the pump housing consistently, neoprene is your safest bet. Natural rubber is out. Plastic might work if it's a high-temp grade, but verify the spec sheet.

Run-Dry Tolerance: What Survives a Blocked Intake

Impellers weren't designed to run dry, but it happens. Seaweed clogs the intake, or you forget to open the seacock. Here's what fails first.

Natural rubber melts. Without water cooling it, friction heat spikes past 70°C in seconds. The vanes fuse to the housing. You'll smell burning rubber.

Neoprene lasts slightly longer—maybe 30-60 seconds—before it starts to harden and crack from the heat. It won't melt like natural rubber, but the damage is permanent.

Plastics can survive a brief dry run better than either rubber. Polyurethane's higher heat tolerance and lower friction coefficient give it a small edge. But "better" is relative—you're still looking at damage after more than a minute or two.

If you regularly risk dry running (shallow water, variable intake depth), consider adding a flow alarm. No material is a good substitute for actual water flow.

Abrasion and Tear Resistance: Matching Material to Grit

This is where most guys get it wrong. They assume "tougher" means "better," but abrasion resistance depends on the type of particles.

Fine, Rounded Sediment

Think silt, fine sand, or clay suspended in water. These particles are small and smooth-edged.

Natural rubber absorbs the impacts without tearing. It flexes around each particle. This is why it's the baseline in mining slurry pumps handling fine, neutral slurries.

Neoprene performs similarly but adds chemical resistance if the water is contaminated.

Polyurethane dominates here. Its hardness resists the grinding action of fine particles, lasting 3-5 times longer than natural rubber in fine silica slurries per technical comparisons. In a marine context, if you're pumping clear harbor water with light silt, plastic is cost-effective and durable.

Sharp, Coarse Debris

Crushed shell, gravel, metal shavings—angular particles with sharp edges.

Natural rubber tears under repeated cuts but resists catastrophic failure. It'll shred slowly rather than crack apart.

Neoprene holds up slightly better due to higher tensile strength, but it's still rubber—it will eventually tear.

Plastics crack. A sharp edge concentrates force on a small area, and the brittle structure fractures. I've seen polyurethane impellers lose entire vane tips after a week in water with coarse shell debris.

If you're in shallow, rocky areas or near dredging, stick with rubber or neoprene. Plastic won't last.

Oil and Chemical Exposure: The Hidden Killers

Fuel, bilge oils, and chemicals attack impellers in ways you don't see until they fail.

How Natural Rubber Fails

The sulfur bonds in vulcanized rubber react with hydrocarbon molecules. The rubber swells as oil penetrates the polymer matrix. The impeller gets soft and loses its shape. It won't seal properly, and flow drops.

UV and ozone do similar damage by breaking surface polymer chains, causing surface cracking. If you store spare natural rubber impellers in an engine room near a generator, the ozone from electrical arcing will age them prematurely even while they sit on the shelf.

Why Neoprene Resists

Neoprene's chlorine atoms create a barrier. Oils can't penetrate as easily. It's the reason marine cooling systems default to neoprene—it tolerates minor diesel leaks, hydraulic fluid contamination, and saltwater simultaneously.

But neoprene isn't universal. Gasoline and strong aromatic solvents (like benzene) can still attack it. And as that diesel mechanic pointed out, stagnant diesel residue in a marina bilge can degrade neoprene over months because the concentration builds up without flow to dilute it.

For heavy fuel exposure—like a fuel transfer pump—nitrile rubber is actually the better choice, though it's less common for water pumps.

Plastics' Chemical Inertness

Polyurethane and most engineering plastics don't react chemically with oils, acids, or saltwater. They're inert. This makes them ideal for chemical dosing pumps or corrosive wastewater. Roughly 150,000 industrial plastic pumps operate in U.S. pharmaceutical, food, and electronics plants for exactly this reason.

The tradeoff is mechanical: plastics wear faster than neoprene under abrasion, even if they don't corrode.

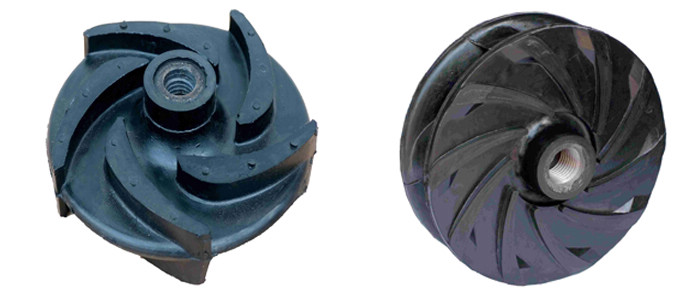

Flex-Crack Resistance: Why Impellers Fracture

Flex-cracking is stress fracture from repeated bending. Every impeller vane flexes thousands of times per hour. Over time, microscopic cracks form at the base of the vanes where stress concentrates.

Neoprene has the best flex-crack resistance of the three. Its molecular structure allows repeated deformation without initiating cracks. If you run your pump daily for months—like a liveaboard or commercial vessel—neoprene justifies the cost by lasting through the season.

Natural rubber is decent but cracks faster under sustained cycling, especially if exposed to ozone or UV between uses.

Plastics depend on the formulation. Soft polyurethanes flex well, but harder grades crack sooner. Once a crack starts in plastic, it propagates quickly because the material can't stretch to redistribute stress.

I've pulled impellers with a single crack at the vane root that split the entire vane off in one piece. That's plastic failure. Rubber tends to tear gradually across the vane surface instead.

Cost vs. Longevity: What You Actually Pay

Natural rubber is the cheapest upfront. If you're on a budget and running a simple freshwater application with no oil and moderate temps, it'll get the job done.

Neoprene costs more—sometimes 30-50% more than natural rubber—but lasts 1-2 times longer in contaminated or saltwater environments per wear studies. Factor in the labor of pulling the pump apart, and neoprene saves money if you value your time.

Polyurethane sits in between. It's cheaper than neoprene, sometimes on par with natural rubber depending on the supplier, and in the right application (clean, fine sediment), it outlasts both by 3-5 times per industrial data.

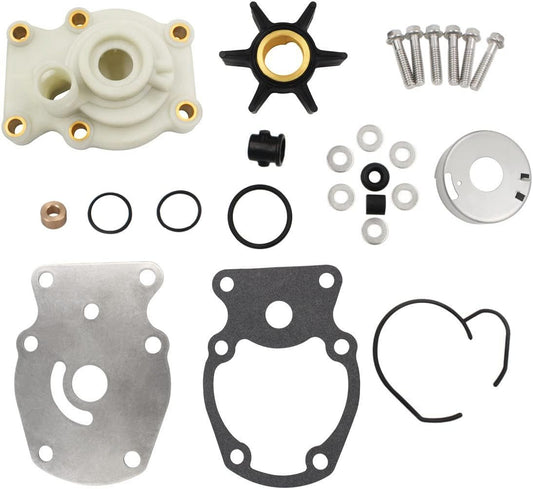

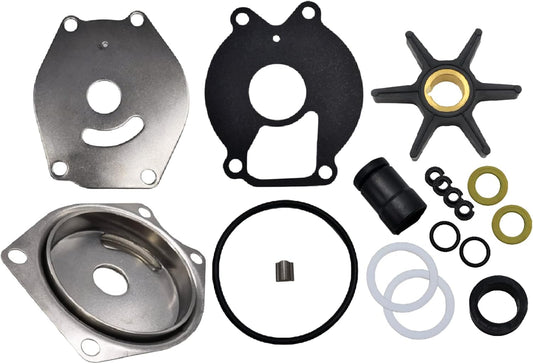

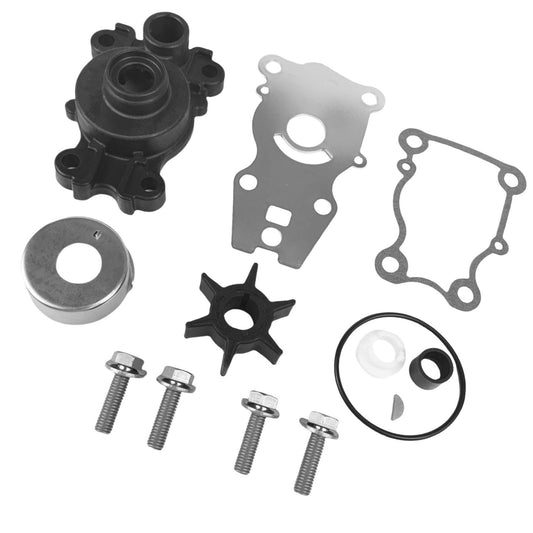

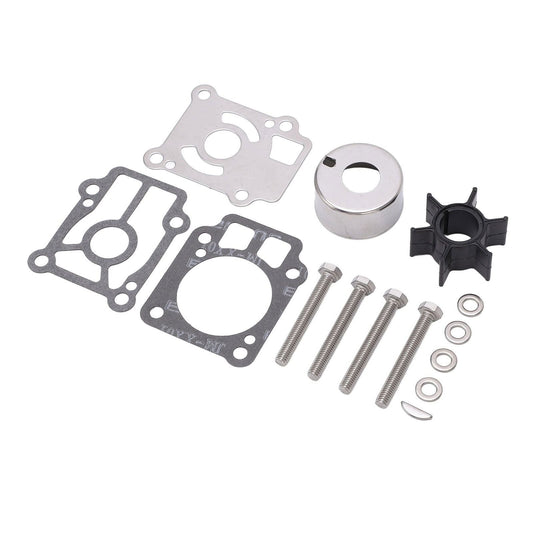

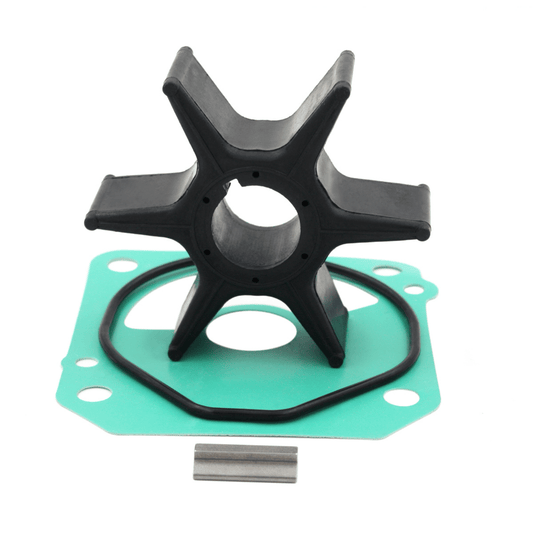

We stock JLM kits that use high-grade neoprene sourced from manufacturers who also supply OEM brands. You get the same material performance without the dealer markup. We shipped a kit to a guy in Australia last week for a 1980s Perkins marine engine—obscure model, but we sourced the neoprene impeller and had it to him in 10 days. That's the kind of access that saves a season. For the best selection of quality marine parts at competitive prices, check out our JLM Marine parts collection.

Don't buy the $10 no-name kits off generic marketplaces. The rubber is often recycled compound with inconsistent Shore hardness. The vanes are too stiff or too soft, and fitment is loose. You'll leak, overheat, or tear vanes within weeks. It's false economy. For advice on reliability and options, see our guide on Are Aftermarket Impellers Reliable?.

Identifying What You Currently Have

Pull the old impeller and look at how it failed. This tells you what it was made of and what went wrong.

Natural rubber that overheated turns sticky and soft, almost tacky to the touch. If it smells like burnt rubber and the vanes are fused or gummy, it's natural rubber that exceeded 70°C.

Neoprene hardens when it fails. It'll be stiff, brittle, and might have surface cracks. If the vanes are intact but hard as plastic and don't flex, it's aged or overheated neoprene.

Plastic chips and fractures. Look for clean breaks at the vane tips or cracks at the root. The edges will be sharp, not torn or ragged like rubber.

Smell can help too. Natural rubber has a distinct sulfur odor, especially when new. Neoprene has a faint chemical smell. Plastics are usually odorless.

Shore hardness is another clue. Press a thumbnail into the vane. Natural rubber (50-70 Shore A) will indent noticeably. Neoprene (60-80 Shore A) is firmer. Polyurethane (80-90+ Shore A) barely gives.

How to Choose: Step-by-Step

Step 1: What's the fluid?

- Freshwater, clean: Polyurethane or natural rubber. Polyurethane lasts longer; natural rubber is cheaper.

- Saltwater or brackish: Neoprene. It resists corrosion and minor fuel contamination.

- Diesel or oily bilge water: Neoprene for general use. Nitrile if diesel contamination is heavy and stagnant.

- Chemicals or acids: Check the specific chemical. Neoprene handles mild acids. For strong acids or unusual solvents, consult a chemical resistance chart for plastics.

- Sandy or silty water (fine particles): Treat it like a fine slurry. Polyurethane for long life; natural rubber for budget.

- Gravel or coarse debris: Natural rubber or neoprene. Avoid plastic.

Step 2: Operating temperature.

- Below 70°C: All three work.

- 70-90°C: Neoprene or high-temp plastic. Natural rubber is out.

- Above 90°C: You need specialized high-temp elastomers (not covered here) or metal impellers.

Step 3: Abrasion type.

- Fine, rounded sediment: Polyurethane wins on longevity.

- Sharp, angular debris: Natural rubber or neoprene.

- Mixed or unknown: Neoprene is the safest middle ground.

Step 4: Durability vs. cost.

- Daily use, long season, commercial: Neoprene. The upfront cost pays off in fewer replacements.

- Weekend use, budget priority, clean water: Polyurethane or natural rubber.

- High-stress, contaminated, variable conditions: Neoprene.

Step 5: Environmental factors.

- UV exposure during storage: Neoprene resists UV and ozone better than natural rubber.

- Fuel/oil leaks: Neoprene or nitrile.

- Clean, controlled environment: Plastic is fine.

Mixed-Use Scenarios

If you run in both fresh and saltwater—like trailering between lakes and the coast—stick with neoprene. You don't want to swap impellers every trip. Neoprene handles both without issue.

Material and Fit: Hardness Matters for Installation

Material choice affects how the impeller fits during installation. Softer natural rubber (50-60 Shore A) compresses easily, so it's forgiving if the housing tolerances are loose. Harder neoprene (70-80 Shore A) requires more force to install, and you'll feel the vanes resist as you slide it in.

Polyurethane at 85-90 Shore A can feel almost rigid. If the fit is tight, lubricating the vanes with water or glycerin helps. Don't use petroleum-based lubes—they can attack rubber during installation.

If your replacement feels significantly stiffer than the original, double-check the material spec. Mismatched hardness can cause sealing issues or prevent the pump from priming.

Avoiding OEM and Cheap Aftermarket Traps

OEM impellers are good quality, but you're paying for the logo. A genuine Yamaha or Mercury neoprene impeller might run $60-80. The material is solid, the fit is guaranteed, but the markup is steep.

Cheap aftermarket—the $10-15 kits from random sellers—use recycled or off-spec rubber. The Shore hardness varies batch to batch. We've seen vanes that are too stiff to flex properly or too soft to maintain pressure. The dimensional tolerances are loose, so you get leaks or poor sealing.

Reputable aftermarket, like JLM Marine, sources from factories that manufacture for OEM brands but sell excess capacity under their own label. Same material, same quality control, but 30-40% cheaper because you're not paying for brand overhead. Our neoprene matches OEM spec: Shore A hardness, temperature rating, and dimensional fit. You're getting the factory part without the dealer price.

We also handle sizing questions. If you lost the part number, email us the engine model and serial number. We'll cross-reference it and confirm the material and size before shipping. That saves returns and downtime. For help with part identification and ordering, visit our main JLM Marine site.

Quick Decision Matrix

| If… | Then Choose… |

|---|---|

| Diesel or fuel present | Neoprene (or nitrile for heavy fuel) |

| Budget priority + cold freshwater | Natural rubber |

| Daily use + saltwater | Neoprene |

| Clean freshwater + fine silt | Polyurethane |

| Sharp debris or gravel | Natural rubber or neoprene |

| High temps (70-90°C) | Neoprene |

| Mixed freshwater/saltwater use | Neoprene |

| Corrosive chemicals | Plastic (verify chemical resistance) |

Maintenance tip: After every saltwater run, flush your raw water system with freshwater for 5-10 minutes. It clears salt crystals that abrade the impeller and eat into the vanes between uses. If you're storing the boat for more than a month, pull the impeller and keep it in a sealed bag away from sunlight and heat. Neoprene especially will take a compression "set" if left installed—it'll flatten on one side and won't seal properly when you restart. For additional maintenance advice, see our Signs Your Outboard Impeller Needs Replacement guide.

For a wide range of marine parts and accessories suited to keep your boat running, explore the Boat Accessories Collection and consider high-quality replacements to maintain performance on all your boating adventures. For expert guides and more content, visit our JLM Marine HUB.

About JLM Marine

Founded in 2002, JLM Marine has established itself as a dedicated manufacturer of high-quality marine parts, based in China. Our commitment to excellence in manufacturing has earned us the trust of top marine brands globally.

As a direct supplier, we bypass intermediaries, which allows us to offer competitive prices without compromising on quality. This approach not only supports cost-efficiency but also ensures that our customers receive the best value directly from the source.

We are excited to expand our reach through retail channels, bringing our expertise and commitment to quality directly to boat owners and enthusiasts worldwide.

Leave a comment

Please note, comments need to be approved before they are published.