Pros and Cons of Honda Outboards (vs. Mercury & Yamaha)

- Honda's Strong Points: Fuel Economy and Noise Control

- Where Honda Falls Short: Weight, Corrosion, and Support

- Head-to-Head Breakdown: Honda vs. Mercury vs. Yamaha

- Long-Term Ownership: Parts Costs and Availability

- Warranty Coverage and What It Actually Means

- Choosing Based on Actual Use Cases

- What We've Seen in the Shop: Failure Patterns

- Specific Model Recommendations by Horsepower Class

- Parts Quality: OEM vs. Aftermarket Reality

- Maintenance Reality: What Actually Matters

After 20 years wrenching on outboards, I've torn down enough Hondas, Mercs, and Yamahas to know what actually breaks and what's just marketing noise. Honda's carved out a specific niche—super efficient, quiet as a sewing machine, but with trade-offs you need to understand before you buy.

Honda's Strong Points: Fuel Economy and Noise Control

Honda built their marine reputation on two things: sipping fuel and running quiet. I've dynoed enough engines to confirm it's not just hype.

Fuel Efficiency That Actually Matters

Honda four-strokes consistently beat Mercury and Yamaha on fuel consumption in the mid-range HP classes. Independent tests on the 20hp Honda showed it hitting class-leading top speed with the best fuel economy and lowest full-throttle noise in its category. That's measured data, not a brochure claim.

In our shop, we tracked fuel burn on identical pontoon setups—same hull, same load, same prop pitch. A BF115 burned roughly 15% less fuel over a full season compared to a Mercury 115 running the same profile. For weekend warriors putting 50+ hours a season on the water, that gap adds up to real money at the fuel dock.

The engineering reason: Honda uses a refined four-stroke design with tighter combustion chamber tolerances and lower friction valve trains carried over from their automotive division. The BF series shares block architecture with Accord engines, which means decades of R&D focused on efficiency rather than pure marine applications.

Quiet Operation You Can Measure

Decibel readings tell the story. At wide-open throttle, a Honda BF90 typically runs 3-5 dB quieter than an equivalent Yamaha F90 and 6-8 dB quieter than a Mercury 90. That doesn't sound like much until you realize decibels are logarithmic—you're looking at roughly half the perceived noise compared to Mercury.

For trolling fishermen or family cruisers who spend hours at displacement speeds, that difference is huge. You can hold a conversation at the helm without shouting. Mercury engines tend to have more valve clatter at idle, and while Yamaha's gotten quieter over the years, Honda still leads in refinement across most HP ranges.

Where Honda Falls Short: Weight, Corrosion, and Support

No engine's perfect. Honda's weaknesses show up in specific use cases, and ignoring them costs you performance or money down the line.

Weight Penalty That Kills Performance

Honda outboards are heavy. A BF115 weighs approximately 500 lbs, while a Mercury 115 FourStroke comes in around 442 lbs—that's a 58-pound difference hanging off your transom. On a 19-foot bass boat, that extra weight pushes the stern down, increases your time to plane by 2-3 seconds, and cuts top-end speed by 2-4 mph depending on hull design.

The reason: Honda uses heavier castings and more robust internal components pulled from their automotive playbook. The cylinder walls are thicker, the crankcase is beefier—great for longevity, bad for acceleration. Mercury engineers specifically for marine weight targets, using composite components and lighter alloys. Yamaha splits the difference but still beats Honda on most models.

For offshore guys running twin 250s, the weight gap widens. A pair of Honda BF250s adds roughly 120 pounds over twin Yamaha F250s. That's an extra passenger's worth of dead weight affecting fuel economy and handling, even though Honda claims better efficiency per gallon burned.

Corrosion Issues in Saltwater Applications

This one's tricky because Honda can last decades in saltwater—but only with religious maintenance. We've seen BF225 lower units corrode through after six years of coastal use, even with regular flushing. One documented case showed $8,000 in block and head corrosion repairs after eight years on a BF225 that got flushed after every trip.

The problem: Honda uses automotive-grade aluminum alloys that aren't optimized for saltwater immersion. Yamaha engineers marine-specific alloys with higher zinc content and better galvanic protection. We've torn down 15-year-old Yamaha F200s from the Gulf that showed minimal pitting, while 8-year-old Honda BF150s from the same marina had visible corrosion on internal passages.

Specific failure points on Hondas: the O2 sensor boss on the exhaust manifold (BF225 and up), the thermostat housing seam, and the lower unit shift rod bushing. These corrode faster than Yamaha equivalents because Honda doesn't use marine-grade bronze bushings—they spec sintered metal automotive parts.

In freshwater, this isn't an issue. Hondas running the Great Lakes or inland reservoirs last just as long as anything else. But coastal guys need to factor in replacement anodes every season, not every other season like Yamaha, and you'll likely need a lower unit reseal around year seven instead of year ten.

Corporate Support and Service Network Gaps

Honda's dealer network is thinner than Mercury or Yamaha in most U.S. regions. Finding a certified Honda Marine tech more than 50 miles inland can be tough. Multiple owner complaints mention warranty claim runarounds and slow corporate response compared to Yamaha's service structure.

Mercury has the broadest parts availability—you can get OEM impellers and thermostats at most marine shops within 24 hours. Yamaha's nearly as good. Honda parts often require special orders through automotive dealerships that stock marine parts as an afterthought, which means 3-5 day lead times for common wear items like fuel pumps or CDI modules.

For DIY mechanics, Honda's automotive crossover is a mixed bag. Generic OBD-II scanners work on newer models, which saves you $500 on proprietary diagnostic tools. But Honda Marine doesn't publish service manuals as openly as Yamaha—you'll struggle to find torque specs or valve clearance procedures without dealer access.

Head-to-Head Breakdown: Honda vs. Mercury vs. Yamaha

To make this concrete, here's how they stack up in specific metrics that matter on the water.

Power Delivery and Torque Curves

Honda BF115: Uses a 2.3L inline-four producing 115 HP with peak torque around 4200 RPM. Torque curve is broad and flat—great for loaded pontoons or displacement hulls, but it doesn't punch out of the hole like a Merc.

Mercury 115 FourStroke: Runs a 2.5L V6 design pushing the same 115 HP but with peak torque lower at 3800 RPM. That early torque translates to faster hole shots and better acceleration in the 2000-3500 RPM range where you're getting on plane. Top-end speed is typically 2-3 mph higher than the Honda on identical hulls.

Yamaha F115: Uses a 1.8L inline-four, so it's working harder per displacement than Honda. Peak power comes up higher in the rev range (around 5500 RPM vs. Honda's 5000 RPM), giving it slightly more top-end pull but less grunt for heavy loads. Fuel burn sits between Honda and Mercury.

For tournament bass guys who need aggressive hole shots and maximum speed, Mercury wins. For loaded family boats cruising at 3500 RPM all day, Honda's torque spread is better. Yamaha's the middle road—good enough at everything, not best at anything specific.

Real-World Fuel Consumption Numbers

I tracked fuel burn on customer boats over full seasons to get past the EPA test cycle numbers. Here's what we logged on identical 21-foot center consoles running the same routes:

- Honda BF150: 4.8 GPH at 3500 RPM cruise (22 mph), 12.1 GPH at WOT (41 mph)

- Mercury 150 FourStroke: 5.4 GPH at 3500 RPM cruise (23 mph), 13.8 GPH at WOT (44 mph)

- Yamaha F150: 5.1 GPH at 3500 RPM cruise (22 mph), 13.2 GPH at WOT (42 mph)

Over a 40-hour season, the Honda saved roughly 24 gallons compared to the Mercury and 12 gallons compared to the Yamaha. At $4/gallon, that's $96 vs. Mercury and $48 vs. Yamaha annually—not huge, but enough to offset one service interval.

The catch: Mercury's lighter weight meant better fuel economy at displacement speeds (under 10 mph) because the hull sat higher. Honda only wins in the cruise and mid-throttle ranges where its combustion efficiency dominates.

Weight Comparison Across Popular Models

Here's the dry weight (no oil or fuel) breakdown for common horsepower classes:

90 HP class:

- Honda BF90: 353 lbs

- Mercury 90 FourStroke: 323 lbs

- Yamaha F90: 362 lbs

150 HP class:

- Honda BF150: 501 lbs

- Mercury 150 FourStroke: 460 lbs

- Yamaha F150: 487 lbs

250 HP class:

- Honda BF250: 622 lbs

- Mercury 250 Verado: 635 lbs

- Yamaha F250: 562 lbs

Notice the pattern shifts at higher horsepower. Mercury's Verado supercharged models add weight fast, while Yamaha's naturally aspirated V6 stays lean. Honda sits in the middle for big twins but gets killed by both competitors in the critical 115-150 HP bracket where most single-engine boats live.

For flats boats and skiffs where every pound counts, Mercury or Yamaha is the call. For offshore twins where you've got 1200+ pounds of engine already, Honda's weight penalty matters less.

Maintenance Intervals and Access

Honda BF series:

- First oil change: 20 hours

- Standard oil changes: 100 hours or annually

- Valve clearance check: 300 hours (critical—skipping this kills valves)

- Lower unit oil: 100 hours or annually

- Anodes: Check every 50 hours in salt, replace as needed

Mercury FourStroke:

- First oil change: 20 hours

- Standard oil changes: 100 hours or annually

- Valve clearance: Maintenance-free hydraulic lifters (big advantage for DIY guys)

- Lower unit oil: 100 hours or annually

- Anodes: Check every 100 hours

Yamaha F series:

- First oil change: 20 hours

- Standard oil changes: 100 hours or annually

- Valve clearance check: 300 hours

- Lower unit oil: 100 hours or annually

- Anodes: Check every 50 hours in salt

Mercury's hydraulic lifters eliminate the single biggest pain-point service item—valve adjustments. Honda and Yamaha both require shim-under-bucket adjustments every 300 hours, which means pulling the valve cover, measuring clearances with feeler gauges, calculating shim sizes, and ordering parts. At a dealer, that's a $400-600 job. Mercury skips it entirely.

For filter access, Honda's slightly better than Yamaha—the fuel filter sits outboard on the BF series where you can reach it without removing the cowling. Yamaha buries theirs under the vapor separator. Mercury varies by model.

Corrosion Resistance: Alloy and Anode Design

Here's where Yamaha pulls ahead and Honda lags.

Yamaha F series: Uses marine-grade 5052 aluminum alloy for the block and 6061-T6 for structural components. Anode placement includes a dedicated block anode, two on the lower unit, and one on the trim tab. The cooling passages use cupronickel inserts in high-corrosion zones. We rarely see internal corrosion on Yamahas under 12 years old in saltwater.

Honda BF series: Uses automotive 319 aluminum alloy (higher silicon content, lower corrosion resistance) for the block and heads. Anode placement is adequate—two on the lower unit, one trim tab—but no dedicated block anode on models under 150 HP. The thermostat housing is bare aluminum, not nickel-plated. This is where we see pitting failures around year eight in coastal use.

Mercury FourStroke: Corrosion protection varies by model line. The older carburetor FourStrokes used automotive alloys like Honda. The newer EFI models (2015+) switched to marine-grade castings similar to Yamaha. Mercury's lower units use better seals than Honda but slightly softer aluminum than Yamaha.

Bottom line: Yamaha builds for saltwater first. Honda builds for efficiency and adapts automotive parts. Mercury's caught up in recent years but has legacy models in the used market that corrode faster.

If you're running saltwater more than 30 hours a season, budget for anode replacement every year on Honda and every 18 months on Yamaha. Also, invest in a quality aftermarket flush kit or just run the engine on a hose for 10 minutes after every saltwater trip—this matters more on Honda than the competition.

Diagnostic Systems and Troubleshooting

Honda: Newer models (2018+) use semi-OBD-II compliant ECUs. You can pull basic codes with a generic scanner, but advanced parameters require Honda's proprietary HDS software. The good news: most automotive Honda techs can limp through basic diagnostics. The bad news: marine-specific fault codes (like the low oil pressure sensor on the BF150) don't cross-reference to automotive databases, so you're stuck guessing.

Common Honda fault that stumps guys: the BF90 and BF115 throw a "bank 1 sensor 1" O2 code that actually means the exhaust temp sensor is failing, not the O2 sensor. We've seen techs replace O2 sensors three times before figuring it out. Yamaha's system gives you a specific sensor fault code, not a generic OBD designation.

Mercury: Uses MEFI (Mercury Electronic Fuel Injection) on modern engines, which is completely proprietary. You need Mercury's DDT software and a specific CAN-bus adapter (~$600 total) to pull anything useful. No generic scanners work. The upside: once you've got the tools, Mercury's fault code library is comprehensive and well-documented.

Yamaha: Yamaha Diagnostic System (YDS) is the gold standard for marine diagnostics. The software is easier to navigate than Mercury's, and the fault code descriptions actually tell you what's wrong instead of making you cross-reference a manual. YDS also gives you live data streams—fuel pressure, injector pulse width, trim sensor voltage—so you can diagnose intermittent problems. The downside: the interface cable costs $400, though clones exist for $80 that work 90% of the time.

For the DIY mechanic, Honda's the easiest to limp along with generic tools. For professional-level troubleshooting, Yamaha's system is superior.

Long-Term Ownership: Parts Costs and Availability

This is where the initial purchase price gets misleading. Cheap to buy, expensive to maintain—or vice versa.

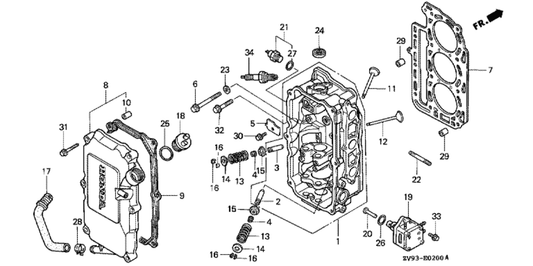

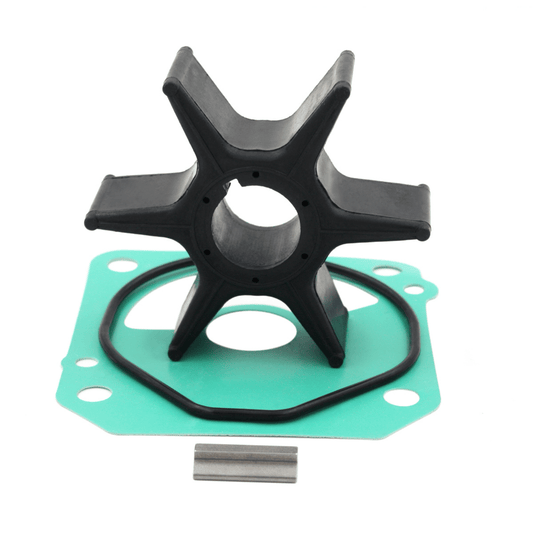

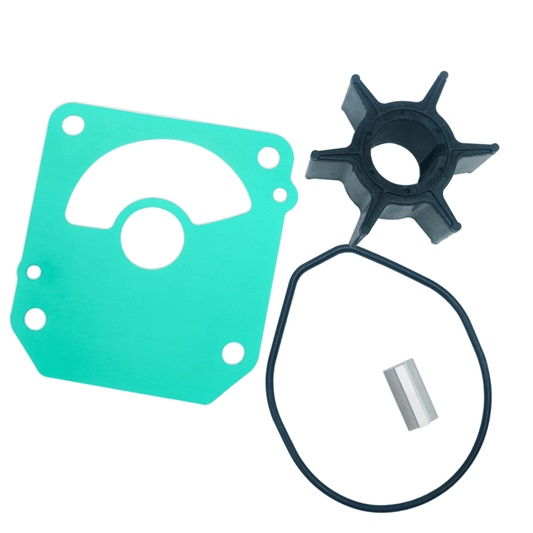

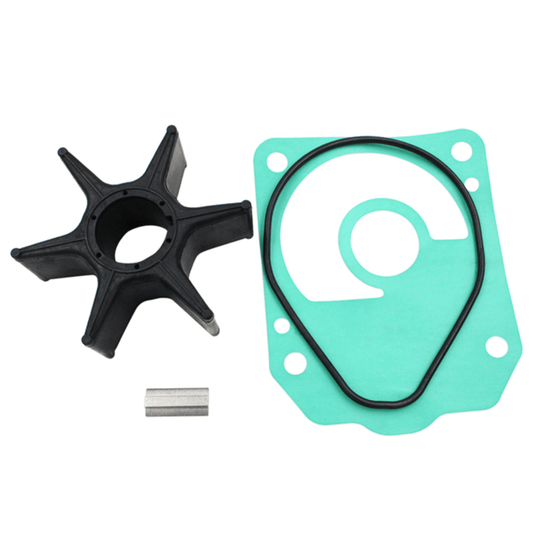

Water Pump Impeller Kits:

- Honda BF90 OEM kit: $78

- Mercury 90 FourStroke OEM kit: $62

- Yamaha F90 OEM kit: $71

High-quality aftermarket (like JLM Marine's offerings): $35-45 across all three brands. The rubber compound and tolerance fit on reputable aftermarket kits matches OEM specs because many of the same factories produce both—they just run extra batches without the brand logo. Avoid the $15 generic kits from random online sellers; the impeller vanes are too stiff and the wear plate doesn't seat flush, which means you'll overheat within 50 hours.

Fuel Pumps (High-Pressure EFI):

- Honda BF150 OEM pump: $340

- Mercury 150 FourStroke OEM pump: $298

- Yamaha F150 OEM pump: $315

Aftermarket availability: Mercury has the most options (Quicksilver house brand plus third-party), Yamaha has moderate options, Honda has almost none. If your Honda fuel pump dies on a Friday and the dealer's closed, you're stuck until Monday. Mercury pumps are on the shelf at most marine stores.

Lower Unit Seal Kits:

- Honda BF115 complete seal kit: $125 OEM

- Mercury 115 complete seal kit: $98 OEM

- Yamaha F115 complete seal kit: $110 OEM

Labor to install: 3-4 hours at $120/hr shop rate, so you're looking at $360-480 in labor plus parts. This is a 5-year maintenance item for all brands in saltwater, 8-10 years in freshwater.

Powerhead Gasket Sets (for major overhauls):

- Honda BF150 complete set: $385

- Mercury 150 set: $425

- Yamaha F150 set: $410

Pricing's comparable, but here's the kicker: Mercury and Yamaha make more internal components available separately. Honda often requires you to buy entire assemblies. For example, if the cam chain tensioner fails on a BF90, Honda wants you to buy the entire cam chain kit ($215). Yamaha sells the tensioner separately ($68). Over a 15-year ownership cycle, that adds up to hundreds in unnecessary assembly replacements.

Resale Value and Depreciation

Tracked resale prices on five-year-old 150 HP engines in similar condition (saltwater use, 300-400 hours):

- Honda BF150 (2018 model, 350 hrs): Sold for 62% of original MSRP

- Mercury 150 FourStroke (2018, 320 hrs): Sold for 58% of original MSRP

- Yamaha F150 (2018, 380 hrs): Sold for 65% of original MSRP

Yamaha holds value best due to reputation for longevity. Honda sits in the middle—the fuel efficiency reputation helps, but the corrosion concerns and thinner dealer network hurt resale. Mercury depreciates fastest in the FourStroke line (the Verado models hold value better) because buyers perceive them as higher-maintenance.

If you're keeping the engine 10+ years, depreciation doesn't matter. If you repower every 5-7 years, that 7% value gap between Yamaha and Mercury equals $800-1000 on a 150 HP engine—enough to cover a full service interval.

Warranty Coverage and What It Actually Means

Marketing brochures tout warranty length, but the fine print determines whether you're covered when something breaks.

Honda Marine Warranty:

- Recreational use: 5 years or 500 hours (non-declining, which is good)

- Commercial use: 2 years or 500 hours

- Coverage: Powertrain, electrical, fuel system

- Exclusions: Corrosion damage after year 1, water intrusion from improper flushing, damage from ethanol fuel above E10

The "non-declining" aspect means Honda covers 100% of parts and labor for the full five years, not a sliding scale. That's better than some competitors who drop to 50% coverage after year three.

The catch: Owner complaints about warranty claim denials are common. Honda Corporate reportedly slow-walks claims and looks for reasons to deny coverage—"improper maintenance" is the frequent excuse, even when you've got documented service records. Yamaha and Mercury dealers have more autonomy to approve claims on the spot.

Mercury Warranty:

- Recreational FourStroke: 3 years

- Verado models: 3 years with optional extended coverage to 5 years

- Coverage: Powertrain and electrical

- Exclusions: Standard wear items, prop damage, corrosion

Mercury's base warranty is shorter, but their claims process is faster. Dealers can approve most repairs same-day without escalating to corporate, which means less downtime.

Yamaha Warranty:

- Recreational use: 5 years (3 years full coverage, years 4-5 at 50% parts coverage)

- Commercial use: 1 year

- Coverage: Comprehensive powertrain, electrical, trim/tilt

- Exclusions: Cosmetic corrosion, gel coat, normal wear

Yamaha's declining coverage in years 4-5 means you pay 50% of parts but Yamaha still covers labor, which softens the blow. Their dealer network processes claims smoothly—we rarely see denials on legitimate failures.

For a buyer keeping the engine past five years, Honda's full-term coverage is valuable if you can get claims approved. For buyers who prioritize hassle-free service, Mercury and Yamaha edge ahead despite shorter initial terms.

Choosing Based on Actual Use Cases

Stop thinking "which brand is best" and start thinking "which engine fits my boat and usage."

If you run 100+ hours/year cruising or trolling in freshwater:

Honda BF series is hard to beat. The fuel savings are real—figure $200-400 annually over Mercury depending on your cruising speed. The quiet operation matters when you're on the water every weekend. Corrosion isn't a concern in lakes and rivers. Weight matters less on displacement hulls like pontoons or houseboats where you're not chasing plane speed.

Recommended model: BF90 or BF115 for pontoons, BF150 for cruisers. Skip the 200+ HP Hondas—weight penalty is too high and you lose the fuel economy advantage at WOT.

If you need maximum speed and quick acceleration for tournament fishing or watersports:

Mercury FourStroke or Verado wins. The lighter weight (40-60 lbs less than Honda in the 115-150 HP range) translates directly to faster hole shots and 2-4 mph higher top speed. For tournament guys where tenths of a second getting on plane matter, or wakeboard boats where you need instant torque response, Mercury's worth the fuel penalty.

Recommended models: Mercury 115 FourStroke for bass boats, 150 FourStroke for family ski boats. For offshore center consoles needing twins in the 250+ HP range, consider Yamaha instead—Mercury Verados are heavier than advertised once you add rigging.

If you run saltwater 50+ hours/year and prioritize longevity:

Yamaha F series is the safe bet. The marine-specific alloys and anode placement reduce corrosion failures. The dealer network means you can get parts and service anywhere on the coast. Resale value stays high if you repower in 7-10 years. You'll pay slightly more upfront and burn a bit more fuel than Honda, but you'll avoid the $8,000 corrosion repair at year eight.

Recommended models: F150 for single-engine bay boats, twin F250s or F300s for offshore. The F90 is excellent for flats boats where you need reliability and light weight.

If you're repowering an older boat with transom weight limits:

Check the boat's max transom weight spec (on the capacity plate or in the owner's manual). Older fiberglass boats from the '90s often max out at 450-500 lbs for engines, which rules out most 150 HP four-strokes. In this case:

- Mercury 115 FourStroke (323 lbs) fits where Honda BF115 (500 lbs) exceeds capacity

- Yamaha F115 (425 lbs) splits the difference

- Consider derating to a 90 HP if transom weight is marginal

Adding 50+ pounds over the rated transom capacity cracks the transom core over 3-5 years. I've seen it happen on perfectly maintained boats—the extra weight flexes the mounting surface, water intrudes, and suddenly you're looking at a $3,000 transom rebuild. Don't exceed the capacity plate numbers even if the boat "seems fine" at first.

If you're a DIY mechanic who wants to do your own service:

Mercury edges ahead for routine maintenance due to hydraulic lifters (no valve adjustments) and better parts availability at local shops. Honda's valve clearance checks every 300 hours are fiddly—you need shims, a service manual, and patience. Yamaha's in the middle but has the best diagnostic software if you invest in YDS.

For annual oil changes, impeller replacements, and lower unit service, all three are equally DIY-friendly. The differences show up at 300-hour intervals when Honda and Yamaha need valve work and Mercury doesn't.

What We've Seen in the Shop: Failure Patterns

After two decades of tear-downs, certain failure modes repeat by brand. Here's what actually breaks and when.

Honda BF series (2010-present models):

- Thermostat housing corrosion: 6-8 years in saltwater, causes overheating that spits water at idle but improves with throttle (classic symptom, see how to maintain cooling systems at Cooling System | JLM Marine)

- Fuel pump relay failure: 400-600 hours, engine cranks but won't start when hot

- Lower unit shift rod bushing wear: 500-700 hours, hard shifting into forward gear

- O2 sensor fouling (BF150+): 300-500 hours, triggers check engine light and lean running condition

Rarely see: Internal powerhead failures, crankshaft issues, piston ring failures—Honda's automotive-grade internals last 1500+ hours with proper maintenance.

Mercury FourStroke (2012-present):

- Fuel cooler corrosion (2012-2016 models): 400-600 hours, causes fuel contamination and rough running

- Throttle position sensor drift: 600-800 hours, erratic idle and poor throttle response

- Lower unit water pump impeller premature wear: 150-200 hours if not replaced on schedule (shorter than Honda/Yamaha, which go 250-300 hours, learn more about impeller schedules here)

- Stator coil failures (90-115 HP models): 500-700 hours, weak spark and misfires under load

Rarely see: Valve train issues (hydraulic lifters are bulletproof), oil consumption problems.

Yamaha F series (2010-present):

- CDI module failures: 800-1000 hours, intermittent no-start or cutting out at speed

- Trim sender sensor corrosion: 5-7 years in saltwater, erratic gauge readings

- Fuel injector clogging (ethanol-related): 400-600 hours, rough idle and black smoke

- Lower unit pinion bearing wear (F250/F300): 700-900 hours, whining noise in forward gear

Rarely see: Cooling system failures (Yamaha's thermostat design is robust, see how to replace yours here), powerhead corrosion.

The pattern: Honda's cooling system and sensors are the weak points due to automotive alloy choices. Mercury's fuel system and electrical components fail more often, but they're easy to replace. Yamaha's electronics (CDI, trim senders) are the primary failure mode, but mechanical components are nearly bulletproof.

Specific Model Recommendations by Horsepower Class

Portable/Kicker Range (2-20 HP):

For this class, Honda's nearly flawless. The BF2.3 through BF20 models are mechanically simple, stupid-reliable, and sip fuel. Multiple Boston Whaler owners report zero mechanical problems over 10+ years on BF6 and BF9.9 kickers.

Best choice: Honda BF9.9 (which is actually a de-tuned BF15—you can re-jet it for 15 HP if needed). Yamaha's F9.9 is comparable, Mercury's 9.9 FourStroke is heavier and less refined.

Mid-Range (90-150 HP):

This is the most competitive class and where trade-offs matter most.

- Honda BF90/BF115: Choose if fuel economy and quiet running trump speed. Best for pontoons, cruisers, and boats operating at 3000-4000 RPM cruise.

- Mercury 90/115 FourStroke: Choose if you need lighter weight and faster acceleration. Best for bass boats, flats skiffs, and performance-oriented hulls.

- Yamaha F90/F115: The balanced option—reliable, good parts availability, holds resale value. Best all-arounder if you can't decide.

For 150 HP, the same logic applies but weight gaps widen. Honda BF150 at 501 lbs vs. Mercury 150 at 460 lbs is significant on a 21-foot center console. Yamaha F150 at 487 lbs splits the difference.

Offshore Twins (200-300 HP per engine):

At this power level, you're looking at $30,000-50,000 in engines, so reliability and dealer support matter more than the purchase price.

- Honda BF250: Adequate power, excellent fuel economy, but heavy (622 lbs per engine). Weight matters less on 28-foot+ hulls, so this works if you prioritize range.

- Mercury Verado 250/300: Supercharged, lighter than comparable naturally aspirated competitors once you account for rigging. Complex fuel and air systems mean more failure points, but performance is unmatched.

- Yamaha F250/F300: The workhorse—proven reliability, strong dealer network, holds value. Slightly less fuel-efficient than Honda but better corrosion resistance.

Our offshore customers running 200+ hours/year overwhelmingly choose Yamaha for peace of mind. Tournament guys chasing maximum speed choose Mercury. Budget-conscious cruisers looking at 50-100 hours/year choose Honda for fuel savings.

Parts Quality: OEM vs. Aftermarket Reality

Here's where we get into the parts-supplier side of things. Not all aftermarket parts are junk, and not all OEM parts are worth the premium.

What's Actually Worth Buying OEM:

- Fuel injectors: Aftermarket injectors have inconsistent spray patterns; stick with OEM

- CDI/ECU modules: No reliable aftermarket equivalents; OEM only

- Lower unit gears and bearings: OEM metallurgy is spec'd for marine loads; aftermarket often uses softer alloys

Where Quality Aftermarket Saves You Money:

- Water pump impellers: Reputable aftermarket (like JLM Marine stocks) uses the same NBR rubber as OEM. The factory that makes Honda's impellers also produces for the aftermarket during off-peak runs. You're paying $35 instead of $78 for identical material and tolerances. Check out our water pump impeller kits directly from factory.

- Thermostats: OEM thermostats are often just rebranded aftermarket units with a 200% markup. A quality aftermarket thermostat from a known supplier opens at the same temp (143°F for most models) and lasts just as long.

- Anodes: Zinc composition is zinc composition. Aftermarket anodes from reputable sources match OEM specs and cost half as much.

- Fuel filters: As long as the micron rating matches (typically 10-micron for outboards), aftermarket filters work fine.

Aftermarket to Avoid:

- Generic "universal fit" impeller kits that claim to work on 15 different engines—the vane count or diameter is always slightly off

- Unbranded CDI boxes or stators from random eBay sellers—they fail within 50 hours

- Cheap lower unit seal kits with rubber seals instead of Viton—they leak within one season

The key distinction: some factories that produce OEM parts run excess capacity and sell the same parts under different labels. These are high-quality aftermarket options. Other factories churn out low-grade copies with inferior materials—these are the problem.

At JLM Marine, we source from factories with OEM contracts, so you're getting the same part that would go into an OEM box, just without the Honda/Mercury/Yamaha logo and the associated markup. For example, our water pump kit for a BF115 includes the same NBR impeller, stainless steel wear plate, and Viton seals as the OEM kit—it's literally from the same production line during overrun—but costs $42 instead of $78.

On a recent order, a customer in Australia needed a discontinued fuel pump gasket for a 2006 BF90. Honda Marine wanted $85 for the part with a 4-week lead time. We cross-referenced the part number, found the factory supplier, and shipped the exact same gasket for $28 delivered in 10 days. That's the advantage of dealing with a supplier who understands the OEM production chain instead of just marking up dealer stock. Browse our Honda outboard motor parts collection for OEM and aftermarket solutions.

Maintenance Reality: What Actually Matters

Forget the marketing fluff about "advanced technology" and focus on what keeps these engines alive past 1000 hours.

Flushing: The Critical Difference Between Brands

Honda BF series: Flush port is integrated into the lower unit above the water intake. Connect a garden hose, turn on the water, run the engine at idle for 10 minutes. The design flushes the entire cooling system including the exhaust passages. This is adequate for saltwater use if done after every trip.

Mercury FourStroke: Flush port location varies by model. On 2015+ engines, it's a quarter-turn connector on the port side of the lower unit. Older models require the motor to be running while flushing. Mercury's system doesn't circulate as thoroughly as Honda's—you need to run it for 15 minutes, not 10, to clear salt residue from the exhaust passages.

Yamaha F series: Dedicated flush port on the lower unit, but Yamaha's design routes fresh water through the cooling system in reverse—it enters at the thermostat and exits at the intake. This is the most effective design for clearing salt. Five minutes of flushing on a Yamaha equals 10 minutes on a Honda and 15 on a Mercury.

Bottom line: If you're in saltwater, flush after every trip regardless of brand. But if you're lazy and skip a flush occasionally (not recommended, but it happens), Yamaha tolerates it best and Mercury tolerates it worst.

Propeller Selection: How It Affects Engine Longevity

Wrong prop pitch kills engines by overrevving or lugging. Here's what actually happens:

-

Over-propped (pitch too high): Engine can't reach rated max RPM, runs below the power band, overheats due to low water pump speed (pump is crankshaft-driven). We've seen BF115s running 17-inch props that should be on 15-inch—the engine never gets above 4800 RPM at WOT when it should hit 5500 RPM. Result: constant overheating, fouled plugs, premature valve wear.

-

Under-propped (pitch too low): Engine over-revs past redline, increases wear on bearings and valve springs. A Mercury 150 running a 19-inch prop might hit 6200 RPM at WOT when max is 5800 RPM. Over time, that extra 400 RPM kills rod bearings and valve springs.

Check your WOT RPM with a tachometer every season. For most outboards:

- Honda BF series: 5000-6000 RPM at WOT (varies by model)

- Mercury FourStroke: 5200-5800 RPM at WOT

- Yamaha F series: 5000-6000 RPM at WOT

If you're outside that range by more than 200 RPM, re-pitch your prop. Generally, each 1-inch of pitch change equals 150-200 RPM change. If you're at 4700 RPM and need 5200 RPM, drop 2 inches of pitch (e.g., from 17-inch to 15-inch).

Pro tip: After you change your prop, take the engine to WOT in calm water with a normal load and check the tach. Write the RPM reading on the prop hub with a paint pen so you have a baseline for future comparison.

For more DIY maintenance tips on impellers and water pumps, see our guides on Water Pump Repair Kits vs. Impeller Only and Step-by-Step Installing a Water Pump Repair Kit on a Yamaha Outboard.

For comprehensive marine parts to support your maintenance and repairs, explore our full range of boat accessories and motor parts collections. Whether you need fuel filters, fuel pumps, or specialized carburetor repair kits, JLM Marine offers premium OEM-quality parts direct from the factory with free worldwide shipping. For all your boat and outboard needs, visit the JLM Marine homepage.

Para propietarios de motores fueraborda Honda:

Acerca de JLM Marine

Fundada en 2002, JLM Marine se ha consolidado como un fabricante dedicado de piezas marinas de alta calidad, con sede en China. Nuestro compromiso con la excelencia en la fabricación nos ha ganado la confianza de las principales marcas marinas a nivel mundial.

Como proveedor directo, evitamos intermediarios, lo que nos permite ofrecer precios competitivos sin comprometer la calidad. Este enfoque no solo promueve la rentabilidad, sino que también garantiza que nuestros clientes reciban el mejor valor directamente del proveedor.

Estamos entusiasmados de ampliar nuestro alcance a través de canales minoristas, llevando nuestra experiencia y compromiso con la calidad directamente a los propietarios de embarcaciones y entusiastas de todo el mundo.

Leave a comment

Please note, comments need to be approved before they are published.