Engine Mount Height and Angle: Tweaking for Better Performance

Why Correct Engine Mount Height and Angle Matter

Most people just bolt the engine down and call it done. That's a mistake. After 20 years wrenching on everything from street builds to full-tilt drag cars, I can tell you that mount height and angle affect everything—how hard you launch, how long your U-joints last, whether you get vibration at 80 mph. It's not about keeping things from rattling. It's about getting power to the ground and keeping your driveline from destroying itself.

Engine Mount Height and Weight Transfer

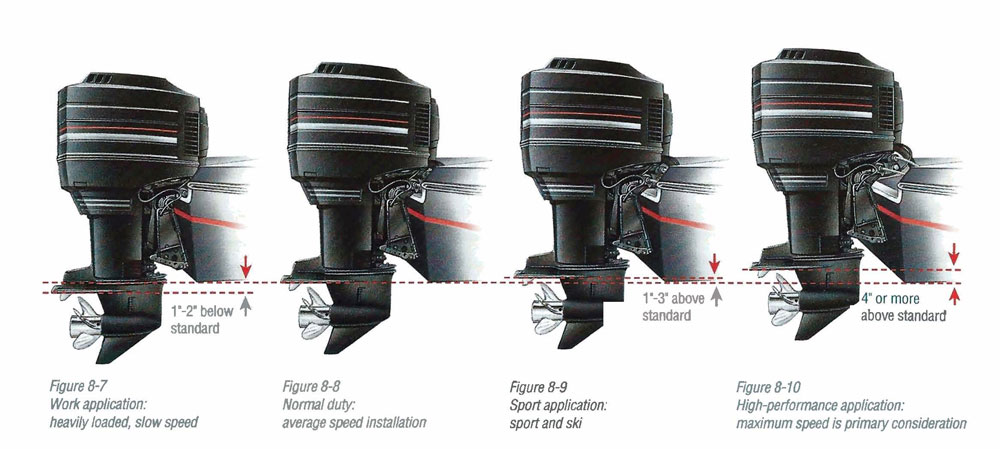

When we talk about engine height, we're measuring crankshaft centerline distance—from the racing surface to the center of the crank snout. In drag racing, this number is critical because it controls how much weight shifts to the rear tires when you launch.

A higher crankshaft centerline raises your center of gravity. That means more weight transfers rearward under acceleration, which is exactly what you want when you're trying to plant the rear slicks and get off the line hard. Most high-horsepower drag setups run crankshaft centerlines between 9 and 12 inches from the ground (Little Setback Engine Mounting Strategies for Drag Racing). The higher you go, the more rear weight transfer you get during launch.

For street cars, the opposite often applies. Aftermarket adjustable height motor mount brackets let you drop the engine by 0.25 to 0.5 inches (adjustable height motor mount bracket). This isn't about weight transfer—it's about hood clearance. If you're trying to squeeze a blower or a tall intake under a stock hood, dropping the engine half an inch can save you from cutting metal or running a cowl hood.

Setting Engine and Transmission Angle

You can't just bolt an engine in level. If you do, you're asking for vibration and dead U-joints.

Here's why: your transmission output shaft sits lower than your rear axle pinion most of the time. If the engine is level, that height difference creates a misaligned driveshaft. The U-joints run at bad angles, which causes vibration at speed and wears the needle bearings flat in a hurry.

The fix is tilting the engine and trans assembly slightly nose-down. We establish a reference line by running a string from the center of the front crank snout to the center of the rear pinion yoke. Then we use an electronic protractor to measure the tilt. For most racecars, you're looking at 1 to 2 degrees of tilt (Little Setback Engine Mounting Strategies for Drag Racing). It doesn't sound like much, but it's enough to align the output shaft with the pinion and keep the driveline happy.

When setting that reference line, attach the string to a specific point on the crank snout—usually a threaded hole or the balancer bolt centerline. On the pinion side, run it to the center of the yoke. Pull it tight. Any sag in the string will throw off your measurement.

Driveline Operating Angles and U-Joint Life

Driveline operating angle is the difference in angle between consecutive shafts. You've got one angle between the transmission output and the driveshaft, and another between the driveshaft and the pinion. These angles need to stay small.

Most driveline manufacturers—Spicer, Dana, Tremec—recommend keeping operating angles at 3 degrees or less for maximum U-joint life (Mastering Driveline Angles). You need at least 0.5 degrees to let the U-joint needles actually rotate and distribute wear, but anything above 3 degrees and you're begging for problems. The higher the angle, the worse the vibration gets at high driveshaft speeds, and the faster the cups start to gall.

Drag racing complicates this because pinion angle changes under load. When you dump the clutch and the chassis loads, the rear suspension compresses and the pinion rotates—what we call "pinion rise." You have to compensate for that rise by setting static pinion angle low.

For ladder-bar setups, you want about 0.5 degrees of pinion angle. Four-link suspensions need 1 to 2.5 degrees, and leaf spring cars can need as much as 6 to 7 degrees because the springs wrap under torque and the pinion rotates more dramatically (Mastering Driveline Angles). Set it right, and your operating angles stay in spec even when you're pulling the front wheels.

Pinion angle measures the angle of the pinion shaft relative to the ground. Driveline operating angle measures the difference between the angles of two connected shafts. They're related, but not the same thing. Confusing them is how you end up with a car that vibrates at 70 mph even though you "set the pinion angle."

Motor Plate Systems for High-Output Engines

Rubber mounts don't cut it once you start making serious power. A stock small-block might be fine on factory bushings, but a 1,200-horsepower engine will tear rubber mounts apart or move around so much you lose consistency.

Motor plate mounting systems replace the rubber with solid aluminum or steel plates that bolt directly to the block and span across the frame rails or subframes. They handle extreme torque and vibration without flexing. They also add structural rigidity to the chassis because they tie the engine directly into critical frame locations (Little Setback Engine Mounting Strategies for Drag Racing).

Stiffness in the mount itself actually improves vibration isolation in some cases. Analysis shows that optimized mount stiffness can reduce vehicle displacement vibrations by as much as 47 percent across the engine's operating range (Optimization Approach for Passive Engine Mounting System). That reduction happens because stiffer mounts prevent the engine from rocking and creating secondary harmonics that resonate through the chassis.

For street cars, motor plates aren't usually practical. The vibration they transmit into the chassis makes the car miserable to drive. Polyurethane inserts in the factory mounts are a better middle ground—they reduce slop without turning the car into a paint shaker.

There's also a tuning consideration: solid mounts can confuse knock sensors on modern EFI engines because they transmit so much mechanical noise. If you're running a tuned ECU, you might need to adjust knock sensor sensitivity to avoid false retard.

Measuring and Adjusting for Precision

You need the right tools. For driveline angles, an angle finder accurate to ±0.25 degrees is the minimum (Mastering Driveline Angles). Digital levels work, but cheap ones drift. We use a Precision Level brand digital protractor because it holds calibration and doesn't zero-creep after you've set five different angles.

For one-piece driveshafts, the goal is keeping the transmission output shaft slope and the pinion shaft slope within 0.5 degrees of each other (Mastering Driveline Angles). Any more and you'll feel it as vibration under load or at cruise speeds.

Physically adjusting height is straightforward if you have adjustable mounts. Loosen the bolts, shim or slot the mount up or down, tighten everything back down. For non-adjustable setups, you're adding shim packs between the mount bracket and the frame or between the block and the mount itself. We've used anything from machined aluminum shims to stacks of steel washers, depending on what the customer had and how much adjustment we needed.

Case Study: Drag Racing Setup

Jerry Bickel builds some of the fastest door cars in the country. His approach to engine mounting focuses on two things: maximizing rear weight transfer and keeping the driveline aligned under acceleration (Little Setback Engine Mounting Strategies for Drag Racing).

For high-horsepower clutch cars, he raises the crankshaft centerline to that 9-to-12-inch range. The higher center of gravity increases rearward weight transfer during launch, which loads the slicks harder and improves 60-foot times.

He tilts the engine and trans assembly 1 to 2 degrees to align the output shaft with the rear pinion yoke. That keeps U-joint angles in spec and prevents vibration at the top end of the track where driveshaft speeds hit their peak.

He also has to stay within NHRA rules for maximum setback from the front spindle centerline. You can't just shove the engine back indefinitely for weight distribution. The rules cap how far rearward the motor can sit, so he balances setback against height and angle to optimize the whole package.

Case Study: Custom Truck Chassis Build

We built a custom truck chassis around a Ford 3.5L EcoBoost last year. Precision in X (fore-aft position), Z (height), and V (pitch angle) was critical for roll center, serviceability, and making sure the intake didn't hit the underside of the hood (custom truck chassis build video).

We set U (roll) and W (yaw) angles to zero to center the engine laterally in the frame. For height, we used adjustable slotted mounts because the customer wanted the option to swap oil pans later without pulling the whole engine. The slots gave us about an inch of vertical travel to fine-tune final height after we test-fit the hood.

Pitch angle (V) was set nose-up slightly to tuck the front of the engine high and away from road debris. The EFI system gave us flexibility—if this had been a carbureted engine, we'd have been stuck keeping the carb level, which would've forced us to compromise on ground clearance.

One specific challenge: the power steering rack on this frame sat close to the oil pan. We had to drop the engine 0.4 inches lower than our initial mockup to get clearance between the pan rail and the steering shaft U-joint. The slotted mounts saved us from fabricating new brackets.

Required Tools for Engine Mount Adjustment

- Socket set (metric and SAE, depending on vehicle)

- Torque wrench

- Digital protractor or electronic level (±0.25-degree accuracy)

- Engine hoist or cherry picker

- Pry bar or long screwdriver for leverage

- String or straightedge for reference line

- Shim stock or adjustable mount brackets

Troubleshooting Engine Mount Height and Angle

How do I know if my engine mounts are bad?

Excessive vibration at idle, during acceleration, or braking. Clunking when you shift or get on the throttle hard. The engine visibly rocks more than it should when you rev it in park. Sometimes you'll feel the shifter vibrate or the steering wheel buzz at certain RPMs if the engine is moving around too much.

Can I adjust my engine height without pulling the engine?

Yes, if you have adjustable mounts. Loosen the bolts, reposition the mount, tighten it back down. For non-adjustable setups, you'll need to support the engine with a hoist, remove the mount bolts, add or remove shims, then reinstall. You don't usually need to pull the engine completely out, but you do need to lift it enough to access the mount hardware.

What tools do I need to adjust engine mount height?

Engine hoist to support the weight. Socket set and wrenches to remove the mount bolts. Torque wrench for reassembly. Digital protractor if you're also setting angle. Shim stock or adjustable brackets depending on what you're working with. A pry bar helps if you need to shift the engine slightly to line up bolt holes.

How often should I check my engine mounts?

Check them during regular service if you're running a performance setup or pushing the car hard. Street cars can go longer, but inspect them any time you notice new vibration or clunking. If you're drag racing, check them every few events. A broken mount at the top end of the track is a good way to grenade a driveshaft or punch a hole in your hood.

What happens if I don't get my engine mount angles right?

Driveline vibration. U-joint failure. Worn transmission output shaft seals. In bad cases, you can crack the tailhousing or bend the driveshaft. You'll also lose power because the driveline is binding instead of transmitting torque smoothly. On a drag car, inconsistent launch angles can cost you hundredths at the tree because the chassis isn't loading the same way every pass.

Are motor plates practical for street use?

Not usually. They transmit too much vibration into the chassis, which makes the car unpleasant to drive. For a dedicated drag car that only sees the street on a trailer, they're great. For a street-strip car, polyurethane mounts are a better compromise—they firm things up without turning the interior into a jackhammer.

What's the budget difference between motor plates and standard mounts?

A good set of polyurethane performance mounts runs $150 to $300 depending on the application. A motor plate system starts around $600 and can go over $1,200 for a full billet setup with adjustable brackets. Add another $200 to $400 for installation if you're paying a shop, because getting the alignment right takes time.

Step-by-Step Adjustment Workflow

- Set Height: Support the engine with a hoist. Adjust mounts or add shims to achieve the target crankshaft centerline height. Tighten mount bolts to spec.

- Set Tilt Angle: Run a reference string from the crank snout to the pinion yoke. Measure engine tilt with a digital protractor. Adjust front or rear mounts to achieve 1-2 degrees of tilt. Verify with the protractor.

- Measure Pinion Angle: With the vehicle on level ground, measure the angle of the pinion shaft. Adjust pinion angle to compensate for suspension type (ladder-bar, 4-link, leaf spring).

- Verify Operating Angles: Measure the angle of the transmission output shaft and the driveshaft. Calculate the operating angle (difference between the two). Repeat for the driveshaft and pinion. Confirm both operating angles are below 3 degrees and above 0.5 degrees.

- Torque Fasteners: Torque all mount bolts and pinion-angle adjustment hardware to manufacturer specs.

- Test Drive: Drive the vehicle at various speeds. Check for vibration, clunking, or unusual noise. Re-measure if issues appear.

Check your mount bolts for proper torque every few months. Heat cycling and vibration can back them off over time, especially on performance engines.

For more outstanding automotive and marine insights, explore the JLM Marine HUB.

Leave a comment

Please note, comments need to be approved before they are published.